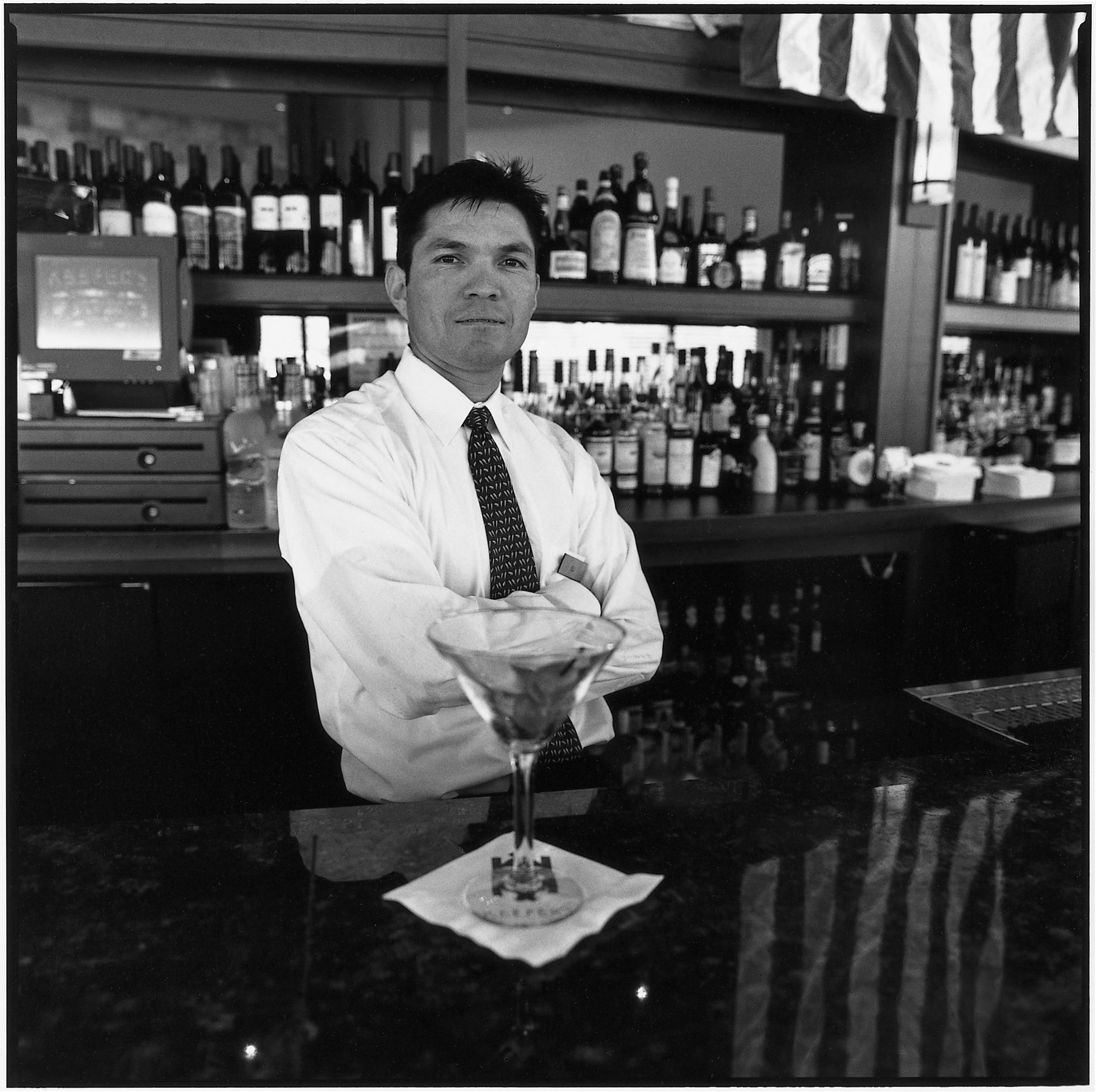

Eli Ramírez

My name is Eli Ramírez and I am from Guatemala. I came here about two years and a couple months [ago] in September ’98, exactly September 3rd I think, yeah.

I was born in a little town in the middle of rain forest and wild rivers in the Department of Retalhuleu, Guatemala. Actually, I just born where I have already told you, but afterwards my dad moved from this town to Quetzaltenango, the second city in Guatemala. He got a job with the government and I was eight months old when we moved to Quetzaltenango and I grew up over there. Quetzaltenango is in the highlands of Guatemala so the weather is cold, especially in summer. And it’s rainy in the winter.

I didn’t live in the city of Quetzaltenango, but about five kilometers away in the countryside pretty near to the city. So [our home] was in the middle of cornfields. There were two bedrooms and I used to sleep in the bedroom with my sisters, and my mom and my dad slept in the other one. At the very beginning, we didn’t have electricity, so we used to light candles at night. And we didn’t have water at home, so we used to go to a pila; it’s kind of the big container of water where all the people went to get water. There was a pipe, but this pipe filled up all this container and people went over there and take water in containers. Public water. We didn’t have a bathroom. Well, actually, kind of bathroom. All the people in that town used to dig a big hole and make a kind of little house on top of it and that was the kind of latrine that we used to have.

I grew up actually with very little commodities. My memories are that we didn’t have refrigerator. My mom used to cook with firewood. We didn’t have stove. We didn’t have TV. Wow. Only a few persons in the town. The most we had is a radio, which worked with batteries. But if I think in relation with my neighbors, I think that at least we had food every day and clothes and we lived sort of better than other people in my town, which was a town of peasants and really poor people who used to live from corn and beans and things that they produced from the earth.

[We had] a little piece of land, but it wasn’t big enough. We used to harvest corn, but it wasn’t enough, so my dad always bought corn from other people and beans and all that stuff. My memories of my meals when I was a child till I was about 12 maybe: beans in the morning, corn tortillas and kind of sauce maybe with tomato, cilantro kind of fried in a little bit of oil. When I think with relation with what I eat now—oh, it’s big difference! We didn’t have really good alimentation.

My dad used to be a mechanic. He worked for Caminos, which is a department of the transportation and roads maintainment. He didn’t start as mechanic. He started working on the roads, cleaning up the sides of the road and all that stuff. And he ascended, climbed up until he became a mechanic. My dad was a silent guy. He didn’t use to speak too much with us. But he was the kind of guy who we used to respect and all our neighbors respected also ’cause he always gave an image of a straight man, and fair, and very careful of his family. Yeah, that was him. From my father, honesty, and hard work, and to be fair with my fellows and responsible toward my family, I think I learned all that about him. We had small conversations sometimes, but mostly watching him. When sometimes he used to rub my head or beat softly my ears, those were the times when I really felt that love that he used to have toward me, but he never expressed it speaking. My dad passed away about four years ago.

My mom is still alive. She is the kind of person that always gave her life for her childrens and she always obeyed my father in everything. She never had a job, never. She was the kind of home woman. She always washed our clothes, made my father’s and our food, and kind of submissive woman ’cause that is the culture in my country. They never had more than the primary school. I think my father studied six years and my mother four or five.

Selling handicrafts. Honduras. 1997

My mom had five children, four women and I in the middle. So I am the only man and I was kind of the guy who my mother and my father loved the most I think ’cause I am the only man, so I was kind of something special in the family. I think my sisters were kind of jealous toward me ’cause they felt like my mom and my dad take more care of me than of them, but they were cool girls. At certain times they took care of me, of course.

My father was a really Catholic to death, and my mom also. So we grew up kind of Catholics, too. I used to say that I was Catholic, but really few times I went to church and I went to hear the misa [mass]. Almost never. I didn’t really like to go to church. Usually they didn’t either, just when there were weddings or bautismos [baptisms] and first communions and that kind of stuff, I think, because the weekends we have to go to a mountain to look for firewood. Well, because my mom cooked with firewood so on the weekends we had to go to a mountain, which is about four miles from my home, and we looked for dry firewood in order of saving money and not buy the firewood from other people. So Saturdays and Sundays early in the morning, my dad and me and sometimes my sisters, too, went to these mountains to look for firewood. Sometimes we cut trees ’cause sometimes it was hard to find enough firewood already cut, because all the people used to cook with firewood, so it was kind of not very common to find dry firewood.

We called this thing mecapal. It’s a kind of piece of leather that we put around our forehead and it was tied to a bunch of firewood and we used to carry that way. And sometimes we used a carreta [wheelbarrow] to bring the firewood. For me it was [hard work] and I think for my father too ’cause after we came from that mountain, we used to have some lunch and my dad rested to get ready for next day to go to work. And I think because that, we never really had time to go to church. [Laughs.]

People and my parents said that I was an imp. You know what is that? Very hyperactive, always making travesuras [mischief] and all that kind of stuff. It means doing something always, and without thinking too much if I broke a glass or a plate or I kicked somebody.

I really liked school. Actually, I went to school after my sisters and I finished school before them. I went a couple of years [to high school], but I didn’t do well. I think it was because I never really had the books, I never really had the uniform, and when I saw another people with all that kind of stuff, I felt kind of mad at myself or disappointed and kind of rebelliousness caught me. [Laughs.] I just dropped out of school. I think sometimes I answered my teachers in a wrong way and they kicked me off the class. So I got in a lot of problems. That was by the time I was about 15 or 16. So I was a rebel.

Besides of girls, [Laughs.] I think I liked language a lot. In fact, I have a lot of diplomas in my house ’cause I won a lot of speech contests. And how you say when you know a poem by heart and you say it in front of public? Recite. So I won a lot of that kind of contests. And actually, my teachers liked me because of that. I went to another [high school] and I say, “Well, I come from Werner Valle Lopez,” which was my [high school]. And I recited saying I came from there. So my [high school] was kind of getting famous because they had a good reciter over there. I like poetry. There is one. It’s called “Cornman.” [Laughs.] Let me think a little bit about it. I can’t remember one of these phrases right now. I’m going to, I’m sure. I won several contests with this poem. Yeah, it’s a beautiful poem.

Maybe from 1965 to 1989, 25 years, more than that, many things were forbidden in my country. Those were very hard times in my country. Those were times when army had the power in my country, and on the other hand there was the guerrilla. So we were in a civil war and it was pretty unsafe. If the army caught you with a book of Che Guevara, for example, or listening protesting music, you could get in a real bad problems with the army.

When I was a teenager, once I was wearing a shirt of camouflage, a shirt with colors of the army, with camouflage colors, green and you know. And I found some people from the army and they asked me what was I doing wearing that shirt. And they told me to take it off and give it to them. And I was kind of unsafe and fearing and I gave them the shirt. It was in a public place and I had to go home with my underwear. And that was the way, army.

In Quetzaltenango, a lot of fights there. There were groups of guerrillas in the mountains. How can I explain this to you? If you wanted to stay alive, you [couldn’t] talk against the government, and there were also a lot of people, we call them orejas [ears], which is the kind of people spying you and looking what you do, ready to tell the army. And so you have to be very careful ’cause army used to kidnap people, kill them, and disappear them. A couple of uncles of mine were disappeared by the army. One of them used to have a rifle and he used to live in the countryside. Somebody told the army that he had a rifle, and army went to caught him ’cause they thought he was guerrilla or he has something to do with guerrilla. And my uncle never, never appeared again. Never. A lot of people from my town disappeared and we didn’t know whether they went to the guerrillas or the army killed them either. So those were really hard times in my country.

I think because the environment that surrounded me as I was growing up, I became a very troublemaker in my country. There were about three years when I used to go out with my friends at night and drink, smoke. We never did drugs, but we used to drink and smoke. And I was always fighting and beating down other guys. Luckily, I never got beated. [Laughs.] I think it was because the environment that surrounded me. You know, newspapers and radio news, sometimes television news, always speak about kidnappings, disappearances, people killing people, and poverty. I think because of that. And my daddy was very busy trying to bring home what we needed, then he never sat and talked to me about these kind of things or how should I behave in front of this situation.

When I left school, my daddy said, “Well, you didn’t want to study, so go to work ’cause I’m not going to sponsor you. You are almost a man and you gotta see what to do.” [I was] 16 or 17. So I start working everywhere in any kind of job. I used to fix crashed cars, painting and that kind of stuff. After that I worked in a bus getting money from the people, the tickets and all that kind of stuff. And I worked in the countryside also for less than a dollar daily, working eight hours in the corn plantations picking. A dollar a day. With a dollar, [you couldn’t buy] much. So maybe I could buy a lunch with a dollar. I had to work maybe one week to be able to buy a pants or a shirt and about 15 days to buy a pair of shoes. At the beginning, I didn’t give my money to my mom or my dad. I just used it for me. There was some money left to go out with my friends. Not much. By that time I didn’t care what kind of job I did. I just wanted to get some money. I learned a lot about a countryside job, harvesting and all that kind of stuff. I think I liked it.

Actually when I was 18, I was in the Boy Scouts movement in my country and they gave me the opportunity of coming to United States in 1988. I was in Washington, D.C., then I came to Chicago for a while, then I went to California. I was here about two months. Well, I liked the country.

To be a Boy Scout is an adventure and this was kind of, wow, exciting. I was going to United States to meet another Boy Scouts and to stay there for a while and go camping. And I got really excited ’cause some friends of mine who were in the Scout movement had came here before and they went back telling stories. “Oh, United States. Big buildings. Nice people. Nice places.” So I was excited at that time.

The first day when I came, [Laughs.] we came to Florida airport and we stayed in that airport for about two hours and then we got in another plane to Washington. And in Washington we stayed in a hotel and, wow! I left the hotel a couple of times without permission, just to go out and walk on the streets and look everywhere. It was exciting for me. Everything [was amazing]. The city, the beautiful city. The streets, neat streets all with pavement and the houses. How the people wear nice clothes. I don’t have memories of watching somebody begging or kind of that, which in my country is very common. That was quite amazing for me. All the environment. And the next day we went to the Washington Capitol and visit some monuments: Jefferson’s, the Washington, and Potomac River, and all those places. It was exciting. And that’s it. After Washington we came to Chicago, just to the airport. I think it was O’Hare, and we took another plane to San Francisco. And we were there a couple of days. I traveled in these kind of trains in San Francisco, the trolleys. And we crossed this Golden [Gate] Bridge and we took several pictures. We went to the Chinatown in San Francisco. I really enjoyed that trip. Two months. [Mostly we were] in a Scout reservation in Santa Clara, California, in the mountains with another Scouts making scouting stuff—camping, going to the mountains, making my own bed out of leaves, and making a kind of camping house with a piece of plastic, and making fire and cooking my food in the mountains, listening to the birds, watching the sunrise, and all that kind of stuff. Being in the mountains was the thing that I most liked about being a Boy Scout.

I didn’t [speak any English]. I came with a group of about 30 people from my country. And a couple of the guys who was taking care of us, they spoke a little bit of Spanish ’cause they were gringos, and we have translators also.

Actually when I was going back, when I was in the Los Angeles airport, a cousin of mine came ’cause he knew I was going back to Guatemala. And he said, “Eli, make a decision. Outside is my truck. Leave the things you have in the plane, leave your luggage, your baggage. Leave your luggage over there. Anyway I don’t think you have too much to lose and go with me and stay here in United States.”

But I was a Boy Scout. And I had made a promise. And I told him, “No, I don’t think I really need to stay here. Maybe someday I’ll be back, but I think this is not a time.” And believe me, I really regret to not go out with him and to stay here. It was in 1988. I think by this time, I should be a citizen at least. But I didn’t. [Laughs.] So I went back Guatemala.

I think that was a really important thing for me when I was a Boy Scout. They taught us the value of the word and the promise we made and all that kind of stuff. It’s kind of the Scout philosophy. So I went home.

After I dropped school, I started working everywhere and anything and this day a friend of mine came and said, “Eli, you want to go with me to Honduras?”

“To do what?”

“To sell the handicraft at a fair, in an open market.”

And I said, “OK, I’ll try.” And I went with him, and that was the way

I get this kind of business. And I worked not only with him but with other people selling handicraft in fairs around Central America. And I worked about two or three years for these guys, and after that I realized that I could have my own business. And I started making my own things, creating my own styles of handicrafts and selling them. I just learned it watching another people and trying to make things at home, and I think the time was important to perfection in this kind of job. But I never really had a teacher, so everything born from me.

What did I do? It’s kind of epoxymil. Well, this kind of paste came from Mexico. It has two parts, one is white, one is green. And you gotta mix them equal parts and [it] became kind of soft paste. And you have about half an hour to work it out ’cause after that time, it start getting hard and hard and hard till it’s completely hard. [I made] several things: lighter cases, knives, and machete sheaths and necklaces, bracelets, earrings. But not everything from epoxymil. I used to work with bamboo also, with little canes of bamboo. I cut them in little equal pieces and I make also necklaces and beautiful earrings. I used to have a shoemaker knife and I used to cut piece by piece by piece of these little canes.

Sometimes my family said, “Eli, you don’t have to be so perfect when you do these things. What you need is to make lots of them! What you need is to sell!” But I never pay attention to them. And I liked to be perfect with my things, and I used to work long times doing one thing till it was perfect for me. And people pay me more money for my job than for other people’s job, who used to produce things in a row, lots of things. I used to have three or four knife sheaths, not a lot of them, three or four, but I got well paid for them. This job could maintain me for hours sitting and working out till it was perfect. It became kind of religion for me. I really liked it. I really, really liked it.

And I met some people from other countries who used to work with this kind of paste also and they said, “Oh, this is beautiful. This, too. You work very well.” I invest a lot of time to perfect this kind of job. I think that when I was performing this job, nothing else was important for me. I didn’t care about what was going on around me. It just gave me kind of an escape from all the stuff and obligations that I had in my head and it gave me kind of peace. [I did this] about four years till I came here.

When I was working in fairs in Guatemala, it was a word of mouth to hear people talking about another country’s fairs. “Oh, there is gonna be a fair in San Pedro Sula, Honduras.” Or “San Jose, Costa Rica, has a very big festival.”

And I started thinking, “If I sell this here, why I can’t sell it over there?” So I started traveling around Central America. What was interesting, I met a lot of peoples and I learned a lot about other countries’ cultures, food. And by that time, I met a lot of girls [Laughs.] from other countries. I told them, “Where are you from? I’m from Guatemala.” And it was kind of nice ’cause you are from another country, and people from other countries like people from other countries, and it wasn’t hard for me to have a girlfriend in another place. I never traveled by plane. I used to travel in buses from town to town till I get the place where I was going to work. You know the landscape when go in a bus. You go and you go, watching everything around you. You stop to eat somewhere and that was cool for me. Sometimes I had to travel two or three days. When I went to Panama once, I had to travel three days in a row passing a lot of places and cities. I used to read a lot when I was a teenager, so I started knowing things and cities and places where I just had read about it. And I liked to talk with people and ask them how is their lives in their countries and what people eat here and all that kind of stuff. And I learned a lot.

With his wife, Dunia, and daughter Bethel,

Guatemala, 1994

My mom, especially, my mom [loved to hear the stories]. ’Cause I was already an adult and I had my own bed, but when I came, so I slept with my mother. And we used to speak almost the whole night, she telling me all the things that had happened while I wasn’t at home, and I telling her about the things I had known, how much money I had made and people that I’d met and people to say, “Hello,” to my mom even when they didn’t know her. And of course, my friends also. I was special when I came back to my country. Sometimes I didn’t make that much money, but it was cool. It was cool.

Getting married was a really nice adventure in my life. [Laughs.] I was working in this festival in Honduras, a big festival, which is called La Ceiba Carnival. It’s a port city in the Atlantic of Honduras. And I had this girl. She was my girlfriend and she used to live in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, and she knew that I was going to be in La Ceiba at this festival. And she came to visit me. She was supposed to be back at home the next day. And, well, we went to dance. I got drunk ’cause I drank some beers. And in the heat of the moment, I asked her for marry me. And she said, “Are you going to hold your word?”

“Of course, you aren’t talking with the liar.” And then I asked her, “Are you going to hold your word also?”

“Oh, yes. I’ll take the risk.” And next day, she didn’t go back home, and her mother was waiting for her. [Laughs.] And we slept together that day. So next day, she said, “OK, let’s get married.” And my pride didn’t let me to go back and I got married.

And we signed up and we were wife and husband. [Laughs.] It was incredible. When I came back home, [Laughs.] I came with wife and I wasn’t really ready for this ’cause my bed was a little bed, and I didn’t have too many things that I needed, and I went to my dad’s house. So that was the story of my getting married.

She [his daughter, Bethel] born in 1994. I think it was the time when the World Cup was being played here in the United States, the football soccer World Cup. I remember that was the day when Brazil was in the final against Italy and my wife was about giving birth and I was in the hospital waiting, but I was thinking of the football game also. I was in a hurry to see my daughter born, and I remember I couldn’t resist. I left the hospital and I went home to see this football game. [Laughs.] And I thought, if it’s a man, I’m going to call him Bebeto or Romario, one of those famous players’ name, but it was a girl. She was born in the time I was watching the football game. [Laughs.] She born in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. And we came to Guatemala a little time after she was born on July 13th, ’94. I brought them to Guatemala and I went to the municipalidad [city hall] of my town and I told them, “OK. Here is my daughter. She was born here.” And they made an act and then she is Guatemalan [Laughs.] and she is Honduran also. [Laughs.] I don’t know if this is going to get her in trouble. [Laughs.]

When I wasn’t at home, my mother-in-law took care of my little girl. But when I was at home, I usually spend the whole day with my daughter—taking care of her, bathing her, changing clothes, giving her the meals, feeding her. I miss those times a lot. My daughter and me were pretty close, pretty close of course.

We started renting a house in Honduras and [my wife] started working, and we got in troubles ’cause sometimes I went out to some festivals and when I came back she wasn’t at home. And she came from her job tired to sleep, and the other morning early go out. So we really started not having enough time together and we started having problems. And then we agreed that we needed a house and not to keep paying rent when we could invest that money in our house. And I think that was the time when this idea born. I was working hard. We had food. My daughter had what she needed. My wife had what she needed also, but I never had money enough to build a house. And in my country, we always hear of people who came back from United States with money, with car, with things and stories that this country you can make much more money than you do over there. Well, one day I decided to come here to try to make some things real—like my house, like a better level of life, to give my daughter better college.

My wife kind of pushed me. I remember that sometimes when we got in conversation she said, “If you don’t go, I’ll go.”

Well, I said, “If she go, I can lose her. What about my daughter? I’m going to have to take care of her.” But she didn’t really mean that. What she wanted was me to come, so that impelled me to come over here.

By the time we decided that I was going to come here, then the problem was the money ’cause I needed to give the coyote [smuggler] about $1,000 over there and pay the rest here. So I started looking for money. I remember that I had a very good festival over there selling handicrafts. I made about $500 and a brother-in-law of mine who is working in a boat around the world, he lent me $800. So in total I had about $1,300 and from the morning to night I had the money.

I remember the day when I left from Tegucigalpa. It wasn’t hard ’cause I think I didn’t really believe that I was going to make the trip,

I was going to get here. Maybe the bottom of my heart I didn’t really want to. So, that last night, I just kissed my daughter, and early in the morning I kissed my wife and I took the bus to Guatemala, stayed a couple of days with my mother, told her about it and left home just with a bag, backpack with couple of pants and shirts. And let’s go.

The next step was to gather with another lot of people who were going to make the same trip. We reunited in a hotel in Quetzaltenango and from there we came to the frontier line, to the border with Mexico in a little town lost in the mountains. And in the night, we crossed one mountain and in the morning next day we were already in Mexico, hidden of course.

The coyote was with us but not all the time. There are people who are called guias [guides]. They are kind of lower than the coyotes, so they are in charge of taking us through these paths and taking us to a certain place. And I saw the coyote in Guatemala. I saw the coyote in México Distrito Federal [Mexico City]. And I saw the coyote in Matamoros, frontera [border] between Mexico and United States. And I saw the coyote in Houston again, just short periods of time. I think he was flying from city to city.

When we crossed the frontier line between Guatemala and Mexico, we gathered with another lot of people. So, in total we were about 100. About 6:00 in the afternoon, we got in a gas truck, in the tank without gas. So this tank was locked. So supposedly this truck was transporting gasoline. I remember that we really had very, very less oxygen and we didn’t have food, just bottles of water. Each one had two bottles of water and we were really close. We couldn’t even move. And we had to make that trip 24 hours. A couple of people older, the older guys, were about dying in that truck ’cause no oxygen. Sometimes I think when the driver found police, immigration Mexican police, he had to lock the tank and police used to knock. “Somebody in there?” And we had to say nothing, remain completely silent. And those moments were when the tank was completely closed. So it was when the oxygen became less and less and less. And it was a tremendous heat inside of it. It was terrible. I think it was one of the hardest parts of that travel. On the top there is a kind of window and it was always open and the air was running inside. But when police showed up, so it’s gotta be closed. Dark, completely dark.

There was a moment when the truck was caught by police and we didn’t know what was going on outside. So we felt like this truck were deviated from its real way. And there was a moment when we didn’t hear any more noise outside. And so we start to wondering what was going on. And it happened that the driver wasn’t anymore in the truck and the truck was parked in somewhere. And that thing was locked. So it was when the panic caught us and oxygen started being less and less. And I don’t know how, but thanks God, we made a hole on top of this tank and we tore, I don’t know how, but we did, and we came out. No driver. It was a solitary place. Sometimes I think we could die over there and nobody had realized till it was too late.

From where this truck left us, was in Puebla. From Puebla to Distrito Federal [Mexico City] we took a bus, five in each bus. And we went to a hotel in Mexico City. It was beautiful ’cause that hotel we had a bed, we had food, we had carpet and nice place to take a shower. We went to the central camionera [central bus station] in México Distrito Federal and we took a bus to Matamoros at the frontier. In Matamoros, we stayed about four days in a room, kind of this big [a small room], and a big patio. And this house was surrounded by a brick wall. The weather was hot. We didn’t have almost food. And a lot of flies everywhere. Garbage. Just one pipe of water. One bathroom that it was broken. There were about 400 people crowded in that small place. Every day we expected our coyote to come and say, “OK, my people. Come on.” The only thing I wanted was get out of there.

Some people thought they were going to die. They spoke about it. “Oh, this trip is getting so hard.” I never talk of that. I had kind of security inside me that I was going to do well in this trip. We became close with so many people, of course, especially women. You know, women is kind of the weak sex. So we had to take care more of them. They were more sensitive, more fragile. Of course, we became very close one another.

Sometimes I thought of coming back. But what I thought of that was I already owed $1,300 and if I came back to home, how was I going to pay this? So, sometimes I doubt about it. Of course when I was in that house expecting for the coyote to come and say, “OK, let’s go,” and he never appeared, so I thought, “What the hell am I doing here? I would be better eating beans and corn in my country in my home with my mom.” Yeah, sometimes that kind of thoughts came to my mind.

Since I was in this small town in the borderline between Mexico and Guatemala, I realized I was in the middle of a lot of people who needed to grab their faith of something, so I became kind of a leader. I started talking with a couple of these people saying, “We should pray. We should make a prayer for all of us. We should ask God for help.” And I started like this with a couple of friends. And among these people came some people who were Protestants in Guatemala. These people is kind of people who pray all the day, believe in God, and all that kind of stuff. So since that point on, we used to pray every night, anywhere, even when we were in the desert, in the mountains, or in that big house.

And people gathered around and they said, “OK, Eli. Please, make a prayer for us.” And I used to pray loud and they hear me and we asked God for help. And sometimes this was very helpful for a lot of us, especially the people who had already lost all kinds of hopes, or who saw this trip was turning very hard. So we used to pray all the nights. And sometimes the coyotes got involved in these kind of things.

It wasn’t a kind of a prayer that I already knew by heart. It’s just spontaneous relating with the moment we were living and what we wanted. If we didn’t have enough food, just asked God for support us.

Let me tell you that I have always believed in God, always, even when I didn’t go to church, or when I don’t believe very much in things that Bible says. But I think this is one of things that my father taught me: There is a God somewhere watching at you and he’s gonna help you whenever you ask him for help. I believe in God, and if I had the opportunity to be a kind of guide for these people, I just did it. I think I had the courage to do this.

After that, they took us to the edge of the river and we crossed the river with kind of neumático [inner tube]. And we crossed the river at night, about 12:00 [midnight]. Actually, we found the Mexican army at the side of the river and they said, “Oh, where are you from?”

“Mexico.”

“OK, where are you going?”

“Well, you know.”

“We are not supposed to let you go.”

“Well, what are you going to do with us?”

“You have some money?”

“Sure.” So everybody gave them some money.

“OK, go.” And they left us.

After we crossed the river we had a big, big walk, a long walk, about 12 hours. We landed in a kind of desert and we stay the whole day over there. It was the place when I told you we started getting these little leeches who sucks you. It was hard. I remember that we ran out of water and there was rainwater, but it was very dirty and it has little leeches, little bugs, and I said to myself, “I would first drink my own urine instead of drinking this water.” And I did. I drank my urine. I urinated in a bottle and I drank it.

And all the guys, “What the hell are you doing?” But I was really thirsty. I didn’t like the taste of my urine, [Laughs.] so next time we went to this water and we take a cloth and put it in the hole of the bottle and water went down kind of filter. And we drank this water and it’s amazing that, at least not me, I didn’t get any kind of infection in my stomach. The hot was very high, no food, and the leeches, a lot of them.

We had to lie, to sleep on the earth. So we slept there and next day they say, “OK, let’s go to the edge of the road. A couple of trucks are going to stop and you have to jump in the truck and lie like this. Fifteen people each truck.” These trucks were kind of high trucks with thick tires. You can see the truck, but you can’t see the people ’cause all the people is lying inside the rear part of it. Not covered. Lying down the truck, the rear part of the truck. Some people had their elbows or their feet stuck with somebody else over. It was very uncomfortable. And we start coming to Houston. [Laughs.]

There were four trucks. Three of them made the trip up to Houston without problem, but the truck where I was going was caught by police. So I remember that we were praying silently inside of us to make this trip. And I remember I started looking at blue light which passes and I knew it was the police, and I get ready to jump out. And I had the feeling that these guys had dogs. [Laughs.] And I didn’t know what I would do if a dog came towards me. Well, coyotes had already told us, “If you hear a siren and you see lights moving red, the driver is going to pull over and stop and you gotta jump out and run, wherever! Run, ’cause it’s the police.” And we actually did, we actually did. It was in a countryside road and we jumped out the truck and we run in a big field of, I don’t know, maybe pineapples or something. None of us was caught by police, none of us. I’m a runner you know, I didn’t have problems. [Laughs.] But there was this woman who was from El Salvador and she was making this trip with her husband. And this woman had her legs kind of, when you have your legs in one position for a long time it gets kind of asleep, cramps. She couldn’t really run, but for some reason the police didn’t caught her. And her husband was pulling her. We walked for about two hours and we gathered in some place.

With his daughter Bethel, Guatemala, 1998

After the police stopped the truck, I started thinking that we were lucky. They didn’t catch us. I was the guy who the guias, one of them especially, trusted. “Eli, about two miles from here there is a gas station. Take this 50 bucks and go over there and buy some water and some stuff to eat. Be very careful.” And I used to walk this distance from the kind of mountain where we were hidden. I went to the gas station and get some stuff and I came back. Whenever he wanted to make a decision, he said, “Hey, Eli. What do you think we should do?” I always helped him. Actually, they took about $400 out of the really price for my trip because this guia told the coyote that I was helping him.

We stayed there for about three or four days till another truck came for us. The guias went to a gas station and they talked by phone and they came. And we went to Houston. First we were in one hotel. They started asking, “Where are you going? Where are you going?” Some people were going to Nebraska, other people to California, others to New York. And I was the only guy who was coming to Chicago because my friend was waiting for me here to pay them. [Laughs.]

There was 15 people who were coming this road and we started the trip in the North American territory. And we left Houston about 7:00 at night and after 12 hours, about 7:00 or 8:00 the next day, the van where I was coming was stopped by immigration police. They saw the license plates. The license plates said Texas. And they thought, “Well, this van. Where is it going or what people go inside of it?” And they stop the truck and they started asking, “Papers. IDs.” [Laughs.] None of us, of course. “OK, where are you from?”

“Mexico.”

“Who is the President of Mexico? What is this? What is that?” Things that coyotes had already talked to us about it and we already knew what were the answers.

Since we start traveling in Guatemala they start talking about this kind of things. “Listen, guys, this is the most common question a migra [immigration officer] can ask you. And this is what you have to say. Please learn by heart an address somewhere from Mexico and tell them this is my address. This is my address. Where are you from? Mexico, Mexico, Mexico! You gotta talk like Mexicans.”

And also we were finding out how Mexicans say this, how Mexicans say that. Some people didn’t do it. Let me tell you, some people didn’t do it. But the weapon of these people was that they remain silent. They said, “We are Mexican.” Nothing else. Then they can’t say anything. Silence. “We are Mexican, Mexican.” That’s it. [Laughs.] I didn’t remain silent. I answered. Most of these people who came this trip was peasant, some farmers, some not very cultured people. So I felt like I was kind of little bit upper.

They sent me to jail. I felt secure because I knew that I wasn’t really making anything wrong. I was just trying to come here and work. And I knew my rights and I knew these people couldn’t take advantage of me nor I wasn’t supposed to answer strange questions or things like that. I knew that. And I was with the police. I took it easy. I said, “Well, it’s OK. I’ll go back to Mexico and try again.” [Laughs.]

We had been already warned about this. This might happen and this is what you might do. So, I knew that if I was on the other side of the frontier line, what I had to do is just try again as many times as I needed. So after that, I never thought about going back to Guatemala. In jail was about 15 more guys, really convicts. They were waiting for complete 60 guys to put them in a plane and fly to Mexico. They gave us food—no bed, but food. I stayed there one day and next day, people was complete and they put handcuffs, the feet also, around our waist with a big chain as if we were criminals. They led us out to the plane. We flew about an hour and a half.

We flew to Laredo and they brought us to the bridge and they take off our handcuffs and said, “OK, go back to Mexico.”

We crossed the bridge. Then, I called my coyote and I said, “Hey, they caught me. What should I do now?”

“OK, go back to Matamoros. In certain hotel, ask for this guy and he’s gonna take care of you.”

And actually, he did. I went back to Matamoros. I remet with this guy over there and I made the trip again. I stayed in the same house with another people of course, none of the guys who came with me, and crossed the river again. When I crossed the river, we started walking again. I got lost, me and other guy. We lost the rest of people. And I was alone in United States without money, without knowing what to do. And we said, “OK. You see that light over there? OK, this is Brownsville, the frontier line. That’s Brownsville. Let’s go over there.” And we start walking. We came to this place. The other guy had some money. We rent a room in one hotel and then he start calling some people he knew. And people came and pick us up. But this was really new people. I didn’t know them at all. Nothing to do with the coyote who brought me from Guatemala.

But anyway, they were coyotes and they said, “Where you going?”

“Houston.”

“You have money?”

“No, but I have a friend who can give you money.”

“OK, give me your number.”

“How much are you going to charge me?”

“$1,000.”

“$1,000 from here to Houston?”

“Yes, $1,000. You want it or you can just leave?”

“No, I want it.” I didn’t know the city, didn’t know anything. I was kind of scared. “OK, $1,000.”

“You know what, $800 for you.”

“OK, $800.”

And again, crossing the desert, the truck, Houston again. When I was in Houston one more time, I talked with my friend and he said, “What happened?”

“Well, immigration caught the van.”

“OK, take a bus. Take a bus.”

The van was charging me $350 and the bus $100. But these coyotes said, “If you go in bus, police is stopping buses every city and asking for papers.”

“Well, the guy who’s paying my trip told me take a bus. I’m going to take a bus.” And they took me to the bus station and I made more than 24 hours from Houston to here. Nobody asked me for papers. And I came here in September [1998].

I was pretty scared when I left Houston. I was sitting in my seat and whenever I saw lights outside the bus, blue lights or red lights, I was kind of, what can I say? It’s this kind of feeling when you are very insecure, when you feel like if the bus jerks, [Laughs.] it’s because somebody is gonna get in the bus and ask for papers. But as the traveling was going on, I started feeling more secure. Nobody asked me for papers. In the bus there were traveling another Mexican people and kind of shy I started talking to them, and getting confident. After five hours I didn’t feel insecure anymore. We were stopping and people get in the bus, people get out and nothing. I got here in the morning, about 5:00 in the morning.

I didn’t talk English at all. I remember some people tried to talk to me in the bus and, “I don’t know what are you saying. No sé lo que ustedes dicen. No entiendo nada inglés.”

Well, in my country I heard of Chicago. Oh, Chicago—big buildings, big city, one of the biggest cities in the world. Wow, I felt very cool. And when I came to the bus station, I called my friend. He was to leave to work, but there was another guy who slept in this room and he said, “OK, I’m going to go for you and I’m going to have a blue handkerchief in my head and I’m going to have a black jacket. If you see me, talk to me.” I didn’t know him.

Some people had told me that here in Chicago there were immigration police always. I knew that they wear green coats, and when I was in the station I didn’t see nobody in green. I behaved natural. I bought some food and I sat and I start eating. And I was eating when this guy came. He was of course very friendly. We are very good friends now. And he said, “OK, let’s go.” And he brought me here. And when we were coming from the station to here, he said, “You know what, Eli? I already have job for you.”

“Where?”

“Where I work.”

“Oh, beautiful. I already have job.” [Laughs.]

“So, you wanna go today?”

“No, no. Today I gotta rest a little bit and eat.” And I stayed the whole day alone here. And next day, I went to Charlie Trotter’s restaurant and that was my first job. [Laughs.]

They said, “Oh, this is the best restaurant in Chicago.” Actually, it wasn’t a bad experience at all. I learned a lot over there. Wash dishes. That was my first job. And after three months, they take me to the polishing room where you have to wipe wine glasses and silverware. And after that, they started thinking of me as a busboy or running food. But always they kept me close to the dish machine. About one in the morning, I had to change my clothes and wear cook clothes, put a funny hat and go to the dish machine and help the guys to close the machine.

When this friend of mine took me over there, he warned me that I needed to go to 26th [Street], to Little Village, and get papers over there. Well, I said, “OK,” and we went. He told me to take a couple of pictures and we went over there. When the car get in the parking lot, there were people signaling like this. And so I realized that these were the guys. They came close and, “Do you need an ID?”

“Yeah, how much?”

“$100.”

And my friend said, “Last time I paid you $80.”

“OK, $80. Give me the money, give me the pictures, come back in half an hour.” And we stayed little bit over there walking around and then we came back. We had the papers. I always used my name. I haven’t changed my name. I haven’t changed my birthday. I don’t know if it’s good or it’s wrong or I don’t know. I think I’m not doing anything wrong, so I’m using my name. Since then, those have been the papers that I have showed to anywhere I had wanted to ask for a job.

I had been going to school about one year and I already knew some English, and I asked my manager, “I know some English. I don’t wanna work anymore on the dish machine. I wanna do something else.”

And he said, “OK.” But these people were very exigent. The first time you take a plate to a table, they want you to do everything perfectly. And of course I was nervous and I did some things wrong ’cause I was a beginner. Because I served maybe in the wrong side. I have to be on the left, with the left hand, not put the elbow in the face of the customer. So they said, “Oh, no. You’re not ready. You gotta wait more.” I felt since that day, he got some kind of angry toward me and he started treating me bad for anything that I made in the restaurant. He laughed at me. One day he said, “No more Spanish in this restaurant. None of you guys.” There were about five Mexicans. “None of you. I don’t wanna hear Spanish in this restaurant.”

And I said, “You know what? I know my rights. You are not supposed to forbid me to talk in our language ’cause sometimes when I have to communicate with these guys, I understand better in Spanish.”

“Yeah, but this is the best restaurant in United States and I don’t want customers to hear you speaking Spanish here.”

I retort him kind of, “Fuck you!” ’cause I was angry. And things start going bad. And after that, I said, “Well, Chicago is a fuckin’ big city. Why should I stay here all my time? There is a lot of restaurants in the downtown. Chicago is not only Charlie Trotter’s.” [My English teacher] helped me to write a resignation letter and I gave it to Charlie and to my manager, the guy who hired me, and said, “Thank you.” They asked me for stay a couple more months. I didn’t want and I left Charlie Trotter’s and I start looking for another jobs and I realized that nowhere people have treated me like those guys treated me there, even when I was always trying to make things good, trying to achieve more knowledge and trying to perform better every day. It wasn’t matter for them.

I have always liked education. As I have told you, I used to read a lot. And when I came here, when I start working as dishwasher over there, I got mad ’cause people talked to me in a slang language and I didn’t know how to answer. And I didn’t even know what they were saying to me. Maybe sometimes just looking at their faces I knew they were angry or saying something bad to me and I didn’t know what was that. So, my friend told me, “I’m going to school. You wanna go to school?”

“Sure, I want to go to school.” And I also heard that if you speak English, you will have better opportunities, you will be a busboy or this or that, earn more money working less hard. But when I went to Truman, there were no inscriptions [registrations]. So I was one month since I came from September to October, and then I start going to school in October. And I made the test. They send me to level 2 and I never left school since then. Those days when I was working at Charlie Trotter’s, I worked from 5:00 [in the afternoon] to 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning, and Truman is far away from here. And I had to take the train. And several times I fell asleep on my desk in my English class. Those were really hard times. And all the money I got from my check, it was to pay my ticket. I wasn’t making that lot of money at Charlie Trotter’s. Several times I thought of getting two jobs and leave school, but I didn’t. And I did not regret that ’cause at this time, I can choose what I want to work and what I wanna do.

I have always asked my friends, “Why do you think this government gives you the opportunity of studying for free? They are not stupid. They know that you don’t have papers. What is the real reason? What is behind this opportunity? You think they are giving something without wanting anything else in change?” Yeah, it’s surprising for me. Of course it is. I don’t know. I have thought of maybe government do this because they want people well prepared to perform jobs ’cause they need workers maybe, or because it’s a way of trying to discover smart people who can import something to North American society in the field of science or something else, art. I don’t know. That’s the kind of feelings that I have. But it’s good for me ’cause it’s for free. And I wonder why even when it’s for free, many people don’t go to school. ’Cause I know a lot of people who I work with, and they don’t care about going to school. They don’t care about culture maybe or...I don’t know.

Since I am in Chicago, I haven’t had a set schedule to talk with [my wife]. Lately, I have been talking to her every 15 days, couple of hours. She thinks I have changed a lot. She says, “Oh, I think you are more smart now. I think you are more mature. You see things different and I think I love you more.” I love her, too.

With two friends from Tuman College, Chicago 2000

In fact, two days ago I was talking with her by phone, and suddenly I made this question to her, “Dunia, how is the house going on?” And she said, “You know what? It already has the roof on it.” Wow! And I got so happy. It’s almost done. And it’s a big house and it’s a good house! And we start this house in May, about six months and it’s already done. And then we started talking about what we had three years ago, how was our life and it’s kind of incredible. It’s almost done. This is the house that we are planning to rent. And we hope it’s gonna be finished in January and then she will move to Guatemala if she don’t get the visa. She’s going to move to Guatemala and build another house over there and wait for me over there. This house is for rent, but it’s a good house, though. I’m really happy. She’s going to send me a video. She promised.

The last months I’ve been able to send $1,000 every 15 days, which is a good amount. I have talked with gringos and they say, “Whew, man! That’s a lot of money!” [Laughs.] Sometimes I think it’s not enough, but it’s kind of a bless from God. I think sometimes life pay us back when we have to face certain things and came over them and make right the things, being fair, trying to be straight in everything. And I think this is the time to harvest ’cause I think my life haven’t been easy, but now it’s better.

When you are here, people over there thinks that here you find money so easy, maybe on the streets. You came here to make money easy, but that is not the true. You have to face several things and obstacles to make money. So I tell them the reality of things. It’s not easy. You gotta be very focused. And you gotta know what you want. And of course, be fair, be honest, things I think I try to be sometimes.

You know what? I have friends who have been longer time than me. For any reason, they don’t have too much. They haven’t built houses or learned English, at least how to write. And in such a short time I have made things that most people don’t do in this period of time. And I think I have some potential inside of me that I need to exploit more and more and more. And I have discovered this here in United States.

But what I would like the most is that my wife and my daughter could come here. She has been trying to, but they have denied the visa to her. So the only thing I say to her is, “Keep trying, keep trying.” If you really want something, I have learned that here, if you want something you have to draw it in your mind. You have to think frequent. You have to tell the people. You gotta write it down and someday it’s going to be real, you are going to reach that. So she’s going to try this day again and I hope this time they do give her the visa.

His daughter, Bethel, Guatemala, 2000

I feel like my daughter haven’t seen me in two years and I think the image of father for her is maybe her uncle or her grandpa. I don’t really know what is going to happen when I go back and I will ask her for some respect or to do something this way or that way. I don’t know how she is going to react. Maybe she has an idea of her daddy, but I don’t know. We talk about how is the school, what have she learned. She used to read some things to me. She is learning English. She knows that I am studying English, too. And she says, “Papi, I’m going to read something in English.” And then she starts [Sings.], “I have a headache. I have a headache right now.” Small things like that. And sometimes she says, “Big hat.”

And I say, “What is that in Spanish?” And then I try to teach her some things.

And then she always said, “Papi, send me a doll.”

“What kind of doll?”

“A Barbie, papi. I want a Barbie.” [Laughs.] You know, things like that. I think my wife is playing a big role in this thing ’cause she is always talking to her about her daddy. And they are waiting for me, and that her daddy loves her and that stuff.

If I think of my daughter, try to understand this. I would like her to study here but to live over there because I love my culture, I love my country, I love how parents grow up their children over there. When you are here and you see that parents are always working or somewhere else, and several times you have to take your children to other people to take care of them. I think that sense of family and parenthood and all that, it’s kind of secondary. But in our country, whew, since a child is born and starts breast-feeding and is always with their parents and everything. I think the education of childrens is better in my country ’cause that sense of family and respect and all that stuff.

If I think of my plans when I came here, if I think of the things that I want to do, then time gets shorter. And when I think that I want to be back with them, then time gets longer. So there are not really special days. Moments, moments. Maybe at night when I go to bed and I start wishing my wife to be beside me, and my daughter, read her a tale, those are the hardest times.

This is America. America is for Americans and for anybody else, why not? As I came to this country, you are always waving the flag of liberty and democracy and human rights and all that stuff [Laughs.] and sometimes it’s kind of contradictory because they are kind of discriminating us in certain way. ’Cause if you live in Europe, you don’t have a problem to get your visa, do you? I don’t think so. But why us? I went to the embassy in my country and my wife’s been trying and no. You have to be rich, wealthy to come here.

I feel like arrogant when U.S.A. people say, “I’m American.” So if they are American, where I am from? I’m American, too, even if I don’t have white skin or golden hair. So it’s not my country. Definitely it’s not my country, but it’s my continent and I’m American. And I feel like I should have an opportunity to be legal here. Why not?

I know the truth is besides of me. The truth is with me. The truth is I’m an honest guy. My only sin is that I don’t have papers or that I don’t have permission to work here, but people in places where I have worked have a very good impression of me. And I’m sure they would like me to be a real citizen to keep working over there in those places. People like how I work. I haven’t had problems with police. I’m paying my taxes. My only sin is that I don’t have papers. And sometimes I think that if United States hadn’t played part in this kind of broken democracy in Guatemala—because the CIA was involved in this—life would be better and a lot different in my country, if they hadn’t. They kicked out our president, Jacobo Arbenz, and they put somebody else to work in order to keep U.S.A. interests over there. And I think sometimes they are guilty in part of this lot of people coming here and me staying here, too. They had the power and they got their nose over there and that is part of the subdevelopment of my country. Things would be better maybe.

Well, if we talk in being a citizen in the sense of having the same opportunities of people who was born here have, yes I do [want to be a citizen], but Guatemala is my country. I love it and I’m proud of born over there and I wouldn’t change my nationality. That’s for sure.

I actually don’t have too many friends here. Actually, my circle of friends is really small, mostly guys from Guatemala and maybe a couple of Mexicans. But I think that people here is kind of not willing to make a relationship, to make friends with. Well, they say they are friends, but they truly aren’t. People is, and sometimes I do to, people is focused on reaching his goals—who has more money, who has better job, who has better cars, who has the world in their hands. Really honest people, a few. I don’t feel like having a lot of friends here.

Sometimes I behave as people do, too, but I’m always open to new friendships. I think this society have taught me to be very careful and kind of doubting when somebody wants to be my friend, like somebody always wants to get something from you. It’s a kind of feeling you know. It’s really different than in my country.

My friends always ask me when I am going to go back. I always tell them, “Three years. I came to stay here three years and then I’ll go back, whether I build my house or I do not.” But [Laughs.] wow, these two years here have changed me in such a way that sometimes I get scared ’cause I don’t think I want to go back anymore. Several things like how much I’m going to earn over there, what am I going to live from there. I don’t think I’m going to fit in that society again. I have my plans also. I think if I go back, I’m going to keep studying, go to university, get a better job. And sometimes I think if I save some money, I’m going to have a good capital to invest in this kind of stuff, and maybe have two or three stalls in two or three different places at the same time.

This is really the country of opportunities. I think everything is possible here. You can do whatever you want here. I mean in the right ways. If you wanna study, you can study. Even if you don’t have papers, you can study. Who doesn’t work here is because he doesn’t want ’cause there is job for everybody. Sources of information and everything is easy to find here, so it’s easy to grow up here intellectually and culturally.

I am happy. I’m very happy because I’m reaching my goals. I feel like I can’t wait to go back home. And I’m going to go back with my mind broadened and knowing a little bit of another language, which would help me over there. And that’s it. I hope [I won’t come back here]. I hope no. But if I need to, I will. I will. I will know how are things here and I will have many doors open. I will have job. Sure, if I need to, I will.